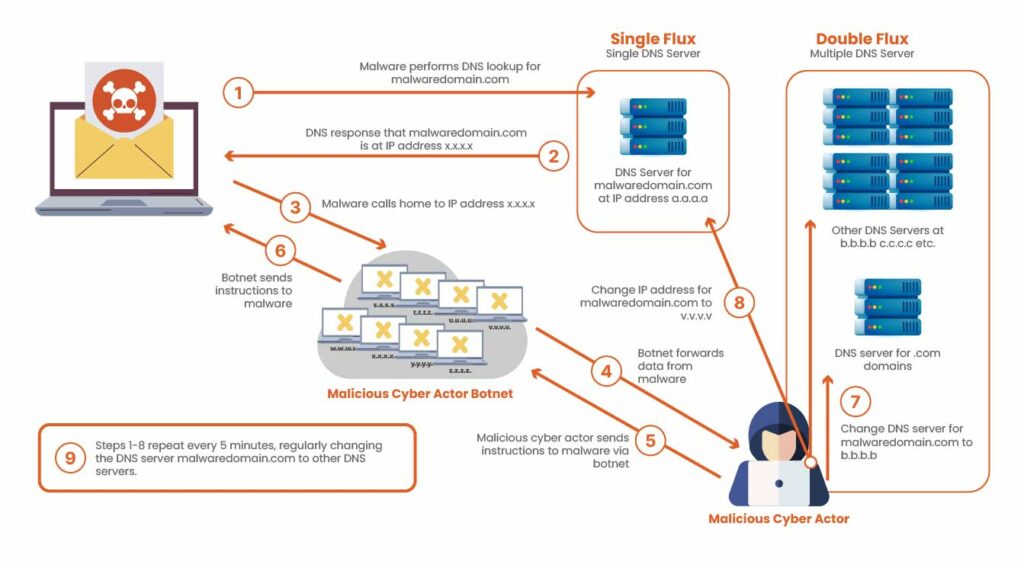

DNS Fast Flux rapidly changes the IP addresses (and even the DNS servers) for a malicious domain, as shown above. Attackers often use compromised machines as proxies, cycling through “hundreds or even thousands” of IP addresses with very low DNS TTL (sometimes as short as 60 seconds). This means each DNS query can return a different IP, turning the domain into a moving target that is much harder to trace or block.

Beyond its traditional association with botnets and bulletproof hosting, Fast Flux has evolved alongside modern internet infrastructure. As organizations increasingly migrate applications to cloud platforms and rely on CDNs for performance, resilience, and global reach, attackers gain a larger surface to hide malicious infrastructure in plain sight. The convergence of Fast Flux techniques with cloud-native features, such as elastic IP allocation, Anycast routing, and distributed edge nodes, has significantly blurred the line between legitimate traffic optimization and adversarial evasion.

Table of Contents

Understanding Fast Flux at the DNS Level

At its core, Fast Flux exploits the flexibility of the Domain Name System (DNS). In a typical Fast Flux setup, a single domain name resolves to multiple IP addresses, and these IPs are rotated rapidly by assigning extremely short Time-To-Live (TTL) values to DNS records. TTLs may be set to just a few minutes or even seconds forcing resolvers to repeatedly query authoritative DNS servers.

Each DNS response returns a different IP address, often pointing to compromised hosts or short-lived virtual machines acting as reverse proxies. These proxy nodes forward traffic to a hidden backend server, such as a phishing site, malware command-and-control (C2) infrastructure, or credential harvesting endpoint. If one proxy IP is blocked, the domain simply resolves to another IP, maintaining uninterrupted availability.

More advanced variants, such as double Fast Flux, rotate not only A records but also NS records, dynamically changing the authoritative DNS servers themselves. This adds another layer of indirection and significantly complicates takedown efforts, as both resolution paths and hosting endpoints are constantly shifting.

Traditional Hosting vs CDN and Cloud Environments

In traditional hosting models, domains typically resolve to one or a very small number of static IP addresses, usually tied to a single physical data center or a fixed hosting provider. DNS records in such environments tend to have relatively long TTL values and rarely change unless there is a planned infrastructure update. As a result, Fast Flux activity stands out clearly. Sudden spikes in IP rotation, abnormally short TTL values, or DNS resolutions that shift across multiple geographic regions are immediate anomalies and strong indicators of malicious intent.

CDN and cloud-based architectures, however, are fundamentally designed around dynamic, distributed infrastructure, which changes the baseline of what is considered “normal” DNS behavior.

Multiple IP Addresses per Domain

CDNs intentionally associate a single domain with a large pool of IP addresses. Each DNS response may return a different subset of IPs depending on the requester’s location, network conditions, or load distribution policies. This behavior closely resembles Fast Flux, where domains resolve to many IP addresses in rapid succession, making IP diversity alone an unreliable detection signal.

Short DNS TTL Values

Short TTLs are a standard optimization in CDN and cloud environments. They allow providers to quickly reroute traffic during outages, mitigate latency, and perform seamless failover. Fast Flux relies on the same mechanism, extremely low TTL values, to rotate malicious IPs rapidly. When both legitimate services and malicious domains use similar TTL ranges, defenders can no longer treat low TTLs as a definitive indicator of Fast Flux.

Anycast Routing and Geo-Based Resolution

CDNs use Anycast routing to direct users to the nearest available edge node. As a result, DNS resolutions for the same domain can vary widely across geographic locations and over short time intervals. This global distribution mimics the geographic churn seen in Fast Flux networks, where IPs frequently shift across regions to evade takedowns and blocklists.

Dynamic IP Allocation and Recycling

Cloud providers continuously allocate, release, and recycle IP addresses as virtual machines and containers scale up or down. From a DNS monitoring perspective, this creates a constantly changing IP landscape. Attackers exploit this elasticity to host Fast Flux nodes on short-lived cloud instances, ensuring that malicious IPs disappear before reputation systems can reliably classify them.

Get in!

Join our weekly newsletter and stay updated

CDN and Cloud Features That Mask Fast Flux

CDNs and clouds offer features that attackers directly leverage for evasion:

Load balancing and auto-scaling:

Attackers host malicious sites on cloud servers or CDN nodes. For instance, an adversary might spin up multiple AWS instances or use Cloudflare Workers, letting the cloud automatically assign new IPs on demand. As Cloudflare explains, round-robin DNS (intended to distribute load) can be “used by attackers to obfuscate their malicious activity.

Cloudflare Tunnels & CNAMEs:

Some actors use Cloudflare Tunnel services or CNAME chains to hide the true origin domain. For example, the Gamaredon group (BlueAlpha) was found using Cloudflare Tunnels so that their malware staging server sat behind a Cloudflare-owned domain, then applying Fast Flux on top of that setup. To any DNS query, the result looks like traffic to Cloudflare, making it blend in.

Dynamic DNS services:

Cloud providers offer their own DNS (e.g. AWS Route 53) with very short refresh intervals. Attackers can mix Fast Flux with dynamic DNS, continuously updating records via API calls. Again, on the surface this looks like normal cloud behavior.

Implications for Fast Flux Detection

Because of the overlap with CDN behavior, defenders must be strategic. Pure DNS heuristics can’t be the only tool. The NSA/CISA advisory suggests a multi-layered approach. In practice, this might include:

Allowlisting Known CDNs:

Maintain a list of legitimate CDN and cloud provider domains/IPs. If a suspicious pattern involves only those known services, analysts can deprioritize it. For example, protective DNS services are advised to “make reasonable efforts…such as allowlisting expected CDN services” to avoid blocking good content.

Threat Intelligence Correlation:

Block domains or IPs already flagged in threat intel feeds, regardless of how many IPs they use. Using reputation can preempt Fast Flux by domain name rather than by its shifting IPs.

Behavioral Analysis:

Look for anomalies beyond DNS. Unusual query patterns, domain age, or associations with phishing campaigns can tip off analysts. For instance, a domain that suddenly starts rotating IPs might be flagged only if it’s tied to an observed email campaign or malware install.

Collaborative Defense:

Share indicators (domains, IPs) with peers and CIRT communities. Fast-Flux domains often have short lifetimes, so quick sharing of IoCs is vital

Book Your Free Cybersecurity Consultation Today!

Conclusion

Fast Flux remains a powerful and effective technique for adversaries, but its true strength today lies in how well it blends into modern infrastructure. CDN and cloud-based setups provide attackers with the same scalability, resilience, and global reach that defenders rely on for legitimate applications.

As long as detection strategies treat Fast Flux as a purely DNS-level anomaly, attackers will continue to hide in the noise of cloud traffic. Effective defense requires understanding Fast Flux not just as a technical mechanism, but as an abuse of trust in modern internet architecture. Only by combining DNS intelligence with behavioral, contextual, and threat-driven analysis can organizations reliably detect Fast Flux in an era dominated by cloud and CDN ecosystems.

FAQs

- How does fast flux work?

A fast-flux network rapidly cycles through a large pool of IP addresses, all mapped to a single malicious domain. While the domain name remains constant, each user connection may resolve to a different underlying IP address.

- How can fast-flux networks be identified?

Multiple techniques, models, and tools have been developed to help detect fast-flux networks, including machine learning–based approaches and dedicated fast-flux monitoring systems. However, no single solution provides universal or foolproof detection.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *